The Guardian: We owe it to the people of Ukraine to bring Vladimir Putin to trial for war crimes

- NGO JAFUA

- Feb 23, 2023

- 4 min read

The special tribunals for Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia show they work. The US must back one for Russia

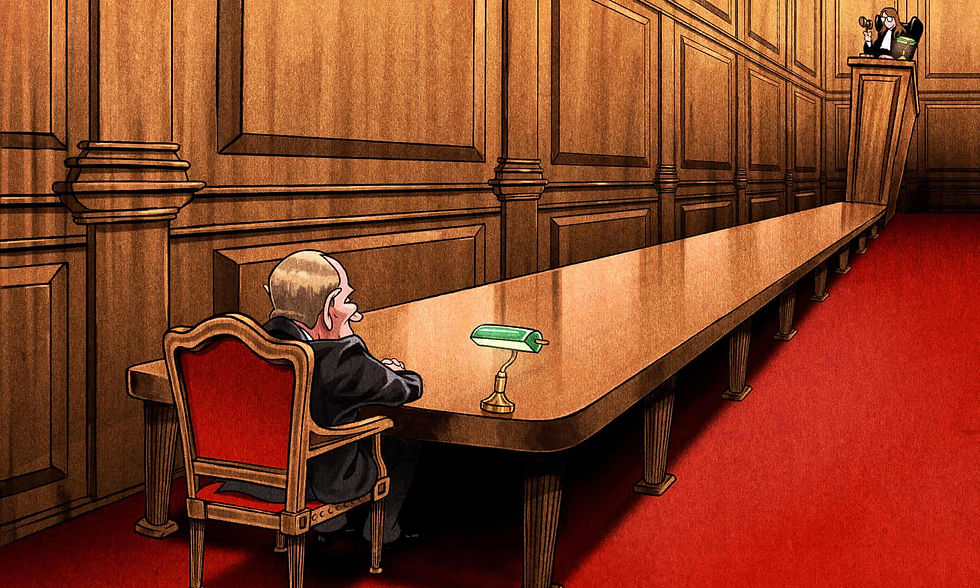

Illustration: Ben Jennings/The Guardian

It is time to bring Vladimir Putin and his enablers to justice – and the US should now take a lead from Europe. Having witnessed first-hand the devastation inflicted on Ukraine, Joe Biden should mark 24 February, the first anniversary of Russia’s invasion, by announcing American support for a special tribunal to try Putin and his henchmen for the crime of aggression.

Biden should make it abundantly clear that there will be no hiding place for those whose invasion has displaced more than 8 million Ukrainians within their own country, and forced nearly 9 million more into exile as refugees. And that there will be no safe haven anywhere in the civilised world for those who are hellbent on inflicting incalculable numbers of injuries and deaths on innocent civilians.

Last month, the UK joined France, Germany, the Netherlands, and the Nordic, Baltic and eastern European countries in endorsing Volodymyr Zelenskiy’s request that the Russian president and his coterie be indicted. The charge sheet, supported by the EU, the European parliament and the Council of Europe, includes the invasion of Crimea and eastern Ukraine in 2014, the planning and declaration of war on Ukraine, and the indiscriminate shelling this winter of its civilian population, designed to starve and freeze them into submission.

The one major western country yet to endorse the tribunal is the US. If it did so, such a tribunal could be constituted within weeks. And there are good reasons why the US – whose vice-president, Kamala Harris, last weekend joined Biden in accusing Putin of “crimes against humanity” – should back this approach.

The crime of aggression is Putin’s original and foundational crime, the one that has been the starting point for all the other atrocities. Aggression is a crime for which evidence is already available, and a special tribunal on aggression that complements the work of the international criminal court (ICC), now investigating war crimes and crimes against humanity, is the best way forward.

Neither Russia nor Ukraine have signed up to the anti-aggression statute of the ICC, so the court does not have the power to prosecute the crime of aggression, and this jurisdictional loophole should be closed.

Special tribunals have been promoted by the US before. Exactly 30 years ago, with the US’s endorsement, the UN security council created the international criminal tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. One year later, it supported the international criminal tribunal for Rwanda. An agreement between the government of Sierra Leone and the UN led to an independent special court and, with the assistance of the UN, special tribunals were created for Cambodia and Lebanon with US support.

But the most obvious parallel is the decision made by nine European allies that met in London in 1942 and drafted a resolution on German aggression, which led, at the war’s end, and with American support, to the creation of the international military tribunal and the trials of Nazi war criminals. The trial of Japanese war criminals followed.

Those who say prosecutions like this do not work should remember not only the verdicts of Nuremberg and Tokyo, but also that the notorious former president of Liberia, Charles Taylor, languishes in a British prison after a 50-year sentence was imposed upon him in 2012 for atrocities committed on his instruction in Sierra Leone. A similar verdict was likely to be imposed on the butcherous Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic, who was being tried in The Hague for war crimes when he died of a heart attack in his prison cell. And war tribunals can sentence criminals in their absence, making it difficult for them ever to travel abroad again.

The US military will probably be advising Biden to resist, worried that such a tribunal would open the door to attempts to prosecute it for actions elsewhere. But the proposed tribunal would not only owe its existence to a request from the Ukrainian government, it would be rooted in the country’s law and lean on customary international law. The crime of aggression would be being applied in the Ukrainian context only.

Others may argue this additional pressure on Putin is counterproductive, upsetting the fine line that Biden continues to walk between defensive assistance and active engagement. And that it would leave Putin less willing to sue for peace.

This would be to misjudge the character of Putin. I first met him in his Kremlin office in 2006 and this, and my dealings with him as chancellor and prime minister, convinced me that all he understands is strength. Similarly, at every turn he is quick to exploit weakness. In every encounter I had with him, threats were the order of the day. Threats to stop gas going west. Threats to sell oil to the east. Threats of retaliation in the event of Nato expansion.

I was never under any illusion: Putin could not be relied on to keep his word and he was not a leader to be trusted. He was determined to return Russia to its superpower status at all costs. His motto appeared to me to be that of Caligula, who rampaged through ancient Rome, murdering anyone who stood in his way: “Let them hate as long as they fear.”

British intelligence told us that he had not only initiated the killing of Alexander Litvinenko in November 2006, but that he was planning further assassinations on the streets of London. It was only by a show of strength on our part – making clear there would be a forceful response to any further attacks and providing years of 24-hour protection for known targets – that most of the threats eased. Sadly, 12 years later, when Britain’s guard had dropped, the Salisbury poisonings took place.

There must be no western weakness this time, and that is why bipartisan pressure is growing within Congress for action, and why a group of prominent Americans will urge the UN general assembly to support such a tribunal.

We owe this to an embattled people now entering a second year under siege. Ukrainian towns and villages have been destroyed, and hearts have been broken, but the spirit and unity of Ukraine’s people have been indestructible. Now, all of us need to summon up similar strength and courage to bring Putin and his henchmen to justice. In a war Russia is losing, this is the intervention they will fear the most.

Comments